M.G. Orender rattles off a list of the great sporting events he has attended: the Super Bowl, the Olympic Games, the Kentucky Derby, the United States Open (tennis and golf), the Daytona 500 and the Indianapolis 500.

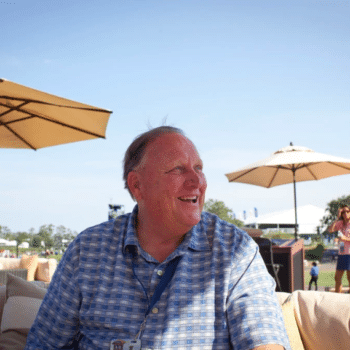

“I’ve had the chance to see about every major sporting event there is,” said Mr. Orender, a founder of the golf course management company Hampton Golf. And he saw them all in style: “I don’t believe I ever went to an event and sat outside the ropes. I always had a seat in the infield or wherever the premier spot was.”

Sporting events have long drawn companies eager to throw up a tent near the action and host clients with food and drink. But in recent years, a desire for an even better and more exclusive experience — at events that are already pretty exclusive — has driven event organizers to create their own private luxury parties and charge handsomely for them. And the red carpet has rolled out to other areas, including concerts, food festivals, art fairs and museum exhibits.

Mr. Orender singled out two of his V.I.P. experiences that did not come cheap: Berckmans Place at the Masters golf tournament at Augusta National, a premium venue within what is already one of the most strictly controlled events in sports, and the Players Club, a luxury package for the Players Championship, a golf tournament being played this week in Ponte Vedra, Fla.

Entry to Berckmans, which has replicas of several of the Augusta National greens inside, is rumored to cost $8,000; the Players Club limits the number of $6,000 tickets it sells to 500 people.

Jared Rice, executive director of the Players Championship, compared the Players Club to packages at other sporting events, but also to the Aspen Food & Wine Festival. “We wanted to have something to match aspirational event seekers,” he said. That includes not only golf fans but those who want to experience any event at its most luxurious.

Unlike many other golf courses, TPC Sawgrass, the course that hosts the Players Championship, was designed with the fan experience in mind, offering spectators views better than most golf events and something more akin to the way they would watch a baseball or football game.

But the Players Club pass, now in its third year, aims to offer a higher level of luxury. There are many vantage points to watch players try to land shots on the 17th hole’s famous island green, which is surrounded on all sides by water. But the Players Club pass puts holders in a club 30 feet in the air, with a cocktail in their hand.

“Year 1 was golf fans,” Mr. Rice said. “But it’s grown to a nontraditional set of fans of sporting events and experiences.”

One of the first organizations to come up with this idea on a large scale was the National Football League, with its NFL On Location program at the 2006 Super Bowl in Detroit.

“The N.F.L. could package its own assets and create a pregame party inside the stadium,” said Frank Supovitz, who created the program.

He said the N.F.L. realized it had extra tickets for V.I.P.s but it also had hotel rooms that were reserved in bulk years in advance. “With multiple venues inside the stadium, we could take all of these things and package them together,” he said. “A ticket that is worth $1,000 is now worth $10,000.”

For that experience to be worth the money, though, Mr. Supovitz said it needed three things: high quality, exclusivity and uniqueness. For instance, at the highest price point for the Super Bowl package, fans get to go on the field after the final down is played.

But this model does not work with all sporting events. The World Series and the Stanley Cup are not as easy for event planners because the location of the games is not known far enough in advance. And with baseball and hockey playing seven-game series for their titles, it’s hard to know when and in which stadium a championship is going to end.

In contrast, the host cities for the Super Bowl are known several years out, and events like the U.S. Open tennis tournament and the Masters are played at the same place every year.

Concerts would seem like a big draw for private events, but for wealthy people, the enticement of briefly meeting a performer backstage is not always enough. Instead, they opt to arrange a private concert for a small group of peers.

These high-dollar events are not limited to sports and music. Art festivals have gotten in on the game by offering an insider’s edge. Pamela Cohen, head of V.I.P. relations and sponsorships at Art Miami, which runs seven fairs in Miami and New York, said her group’s platinum packages cost $5,000 a ticket and give buyers access to private receptions and conversations with well-known artists.

But the real value to serious collectors is the preparation her team does to accommodate connoisseurs before they arrive — knowing which works or artist they would be most interested in seeing, and making it happen. “We do almost all of the work for them and give them an easy, short time to see everything they want,” she said. “We’re really providing that curated experience for them.”

Some exclusive art events work differently. The Brooklyn Museum, for instance, is selling a premium $2,500 ticket to its David Bowie exhibit that gives two patrons access to the show when the museum is closed to regular visitors. It also includes Bowie merchandise and a private guide.

Masha Rubtsova, the general manager of Indochine restaurant in Manhattan, which Mr. Bowie frequented, said she recently went to the exhibit with a friend. On a tour with the museum’s “Aladdin Sane” ticket, she ran into people from the restaurant world and was able to network.

The show itself felt more like a nightclub than an art gallery. “It was crowded but in a good way,” she said.

Super fans are certainly willing to pay more for an elite event, but people who go just for the experience can become jaded and more demanding. Some companies that use high-priced events as a marketing tool have had to add even more exclusive events to their roster to compete.

Consider private jet companies like NetJets and Wheels Up. Both had big V.I.P. facilities at the Masters and big parties featuring professional golfers and television commentators. NetJets hosted the Zac Brown Band one night, while Wheels Up recreated Rao’s, the exclusive East Harlem restaurant, by flying the chef and staff down to Augusta, Ga.

Both companies also have parties at the Super Bowl and the Art Basel art fair in Miami Beach, Fla.

“The No. 1, 2 and 3 reasons for these events are retention, retention, retention,” said Kenny Dichter, chief executive of Wheels Up. “If people show up, they’ll always renew.”

But if other jet companies — and luxury purveyors in general — are throwing the same great parties at the same exclusive venues, the events lose their unique appeal.

After a five-figure initiation fee, Wheels Up charges $4,500 to $7,500 an hour. Another industry rival, VistaJet, which aims for a more global client and so has bigger jets, charges $12,000 to $19,000 an hour.

To woo their well-heeled clients, such companies create events so intimate that they beggar belief. Want to play tennis with Roger Federer? NetJets has organized that. If you’d prefer Serena Williams, Wheels Up has set up private events with her.

Then there were private viewings of the David Rockefeller collection before it went to auction this week at Christie’s. To see it all meant hopping among international destinations, and VistaJet took care of it.

“In London, 20,000 people saw it, but I arranged a dinner for 12 people in Christie’s ballroom with the head of Christie’s London and the head curator of the Rockefeller auction,” said Matteo Atti, executive vice president for marketing and innovation at VistaJet. “I put people in the room who might like each other.”

And for many, that’s the cachet: rubbing elbows with other equally wealthy people who may have shared interests or present a business opportunity.

Of course, sometimes the bar is not that high. Mr. Orender recalled a simple perk of having exclusive access to the Olympic Games: “There was a special line so no one was hassling you and you didn’t have to wait to go in.”

Read Full Article in The New York Times